Splendors of Morocco, March 30 - April 4, 2018

This spring a two-week Moroccan adventure introduced me to the sights and sounds of the country's cities and towns with their medinas and souks, minarets and mosques; to Roman ruins at Volubilis in the north and to those of the ancient trade route town of Sijilmassa in the south; to the kaleidoscopic variety and complexity of zellige tile patterns, carved plasterwork, beamed and painted wooden ceilings. I was amazed by the diversity across the country: the lushness of riad house interior gardens and the greening of the desert countryside in the river oases; the cultivated olives groves and alpine pastures; the open, rocky stretches that looked like the American southwest with great canyons cut by meandering rivers; the desert dunes at the edge of the Sahara; and fields cultivated with blossoming fruit trees and yellow crops.

Before going to Morocco I decided that my journal/sketchbook would take the format of a Persian illuminated manuscript. I was also inspired by the artist Delacroix's illustrated 1832 journal when he accompanied a French diplomatic mission to the country. His pages are filled with architectural details, men and women in local dress, landscapes, and color notations. Not having time to sketch during my trip. I created this journal upon my return from Morocco over a period of four weeks using photographs from the trip as inspiration. There was so much more I could have documented, but I believe the pages of this journal reveal the richness of all I saw in Morocco.

With this post I would like to take you on my adventure through the pages of my sketchbook. Many authors--Ibn Battuta, Leo Africanus, Edith Wharton, Tahir Shah, Fatima Mernissi, and Raquel Cepeda have described Morocco so lyrically that I have chosen to use their words as accompaniment to my illustrations.

I hope you enjoy this journey.

"To visit Morocco is still like turning the pages of some

illuminated Persian manuscript all embroidered with bright shapes and subtle

lines."

"Morocco

is too curious, too beautiful, too rich in landscape and architecture, and

above all too much of a novelty, not to attract one of the main streams of

spring travel…"

Rabat

"…the

great El-Mansour, was a conqueror too, but where he conquered he planted the

undying seed of beauty. The victor

of Alarcos, the soldier who subdued the north of Spain, dreamed a great dream

of art. His ambition was to bestow

on his three capitals, Seville, Rabat, and Marrakech, the three most beautiful

towers the world had ever seen, and if the tower of Rabat had been completed,

and that of Seville had not been injured by Spanish embellishments, his dream

would be been realized.

The

“Tower of Hassan” as the Sultan’s tower is called, rises from the plateau above

old Rabat, overlooking the steep cliff that drops down to the last winding of

the Bou-Regreg. Truncated at half

its height, it stands on the edge of the cliff, a far-off beacon to travelers

by land and sea. It is one of the

world’s great monuments, so sufficient in strength and majesty that until one

has seen its fellow, the Koutoubya of Marrakech, one wonders if the genius of

the builder could have carried such perfect balance of massive wall-spaces and

traceried openings to a triumphant completion.

Near

the tower the red-brown walls and huge piers of the mosque built at the same

time stretch their roofless alignment beneath the sky. This mosque, before it was destroyed,

must have been one of the finest monuments of Almohad architecture in Morocco..."

Chella

"The

ruins of Chella lie on the father side of the plateau above the native town of

Rabat.

Passing

under the gate of Chella, with its richly carved corbels and lofty crenellated

towers, one feels one’s self thus completely reabsorbed into the past.

Below

the gate the ground slopes away, bare and blazing, to a hollow where a little

blue-green minaret gleams through fig-trees, and fragments of arch and vaulting

reveal the outline of a ruined mosque.

The

ruins of Chella belong to the purest period of Moroccan art. The tracery of the

broken arches is all carved in stone or in glazed turquoise tiling, and the

fragments of wall and vaulting have the firm elegance of a classic ruin. But what would even their beauty be without

the leafy setting of the place?

The “unimaginable touch of Time” gives Chella its peculiar charm: the

aged fig-tree clamped in uptorn tiles and thrusting gouty arms between the

arches; the garlanding of vines flung from column to column; the secret pool to

which childless women are brought to bathe, and where the tree springing from a

cleft of the steps is always hung with the bright bits of stuff which are the

votive offerings of Africa.

The

shade, the sound of springs, the terraced orange-garden with irises blooming

along channels of running water, all this greenery and coolness in the hollow

of a fierce red hill make Chella seem, to the traveler new to Africa, the very

type and embodiment of its old contrasts of heat and freshness, of fire and

languor."

"For once, there had been tranquility in my

absence. Rachana said the

guardians had been preoccupied with watching a stork which had begun to build a

nest on top of the roof. They

spent all their time straining against the bright winter light, to get a glimpse

of the great white bird.

'Allahu

Akbar! God is great!”'Marwan shouted. 'This is a blessing on the house, and a great thing for us all.'

The

guardians regarded it as a miracle, and forced me out of bed to come and

see. The bird was sitting awkwardly

on the nest, rearranging itself, trying to get comfortable.

'She’s

happy,' said Osman under his breath. 'She’ll stay here now.'

'I

wonder why she’s chosen our roof,' I said.

Marwan

cleared his throat. 'Dar Khalifa has Baraka,' he said.

Explaining

the idea of Baraka is not easy.

It’s a notion found in Islam, but must surely be pre-Islamic: the idea

that a person, creature, or thing is blessed. The blessing runs so deeply that it touches every cell,

every atom, so that any association with that thing extends the blessing on to

you."

Kasbah

of the Oudayas

"The

European town of Rabat, a rapidly developing community, lies almost wholly

outside the walls of the old Arab city.

The latter, found in the twelfth century by the great Almobad conqueror

of Spain, Yacoub-el-Mansour, stretches its mighty walls to the river’s

mouth. Then they climb the

cliff to enclose the Kasbah of the Oudayas… Great crenellated ramparts,

cyclopean, interrupted by a gate-tower resting on one of the most nobly decorated

of the horseshow arches that break the mighty walls of Moroccan cities. Underneath the tower the vaulted

entrance turns, Arab fashion, at right angles, profiling its red arch against

darkness and mystery."

"The

past is buried deep within the ground in Rabat, although the ancient walls in

the old city are still standing, painted in electrifying variations of royal

blue that make the winding roads look like streamlets or shallow ocean water."

"Nobody

is in the streets wandering from ghostly passage to passage, one hears no step

but that of the watchman with staff and lantern. Presently there appears, far off, a light like the low

flying firefly, as it comes nearer, it is seen to proceed from the Mellah lamp

of open-work brass that a servant carries ahead of two merchants on their way

home… The merchants are grave men, they move softly and slowly on their… slippered feet, pausing from time to

time in confidential talk. At last

they stop before a house wall with a low blue door barred by heavy hasps on

iron. The servant lifts the lamp

and knocks."

Volubilis

"After

a time we left the oueds and villages behind us and were in the mountains of

the Rarb, toiling across high sandy plateaus. Far off a fringe of vegetation showed promise of shade and

water, and at last, against a pale mass of olive-trees, we saw the sight which,

at whatever end of the world one comes upon it, wakes the same sense of awe:

the ruins of a Roman city.

Volubilis

(called by the Arabs the Castle of the Pharaohs) is the only considerable Roman

colony so far discovered in Morocco. It stands on the extreme ledge of a high

plateau backed by the mountains of the Zerhoun. Below the plateau, the land drops down precipitately to a

narrow river-valley green with orchards and gardens, and in the neck of the valley,

where the hills meet again, the conical white town of Moulay Idriss, the Sacred

City of Morocco, rises sharply against a wooded background."

Meknes

"In the year 1701, Ezziani writes,

'The

Sultan… occupied himself personally with the construction of his palaces, and

before one was finished he caused another to be begun. He built the mosque of Elakhdar; the

walls of the new town were pierced with twenty fortified gates and surmounted

with platforms for cannon. Within

the walls he made a great artificial lake where one might row in boats. There was also a granary with immense

subterranean reservoirs of water, and a stable three miles long for the Sultan’s

horses and mules; twelve thousand horses could be stabled in it. The flooring rested on vaults in which

the grain for the horses was stored… All around the stables the rarest trees

were planted. Within the walls

were fifty palaces, each with its own mosque and its baths. Never was such a thing known in any

country…'"

"M.

Augustine Bernard, in his admirable book on Morocco, says that the seventeenth

century was 'the golden age of piracy' in Morocco; and the great Ismael was no

doubt one of its chief promoters.

One understands his unwillingness to come to an agreement with his great

friend and competitor, Louis XIV, on the difficult subject of the ransom of

Christian captives when one reads in the admiring Ezziani that it took

fifty-five thousand prisoners and captives to execute his architectural

conceptions.

The

English emissaries appear to have been much struck by the magnificence of his

palaces, then in all the splendor of novelty, and gleaming with marbles brought

from Volubilis and Sale. [John]

Windus extols in particular the sunken gardens of cypress, pomegranate and

orange trees, some of them laid out seventy feet below the level of the

palace-courts; the exquisite plaster fretwork; the miles of tessellated walls

and pavement made in the finely patterned mosaic work of Fez; and the long

terrace walk trellised with 'vines and other greens' leading from the palace to

the famous stables…

'These

prisoners, by day, were occupied on various tasks; at night they were locked

into subterranean dungeons.'

Moulay

Ismael received the English ambassador with every show of pomp and friendship,

and immediately 'made a present' of a handful of young English captives; but

just as the negotiations were about to be concluded Commodore Stewart was

privately advised that the Sultan had no intention of allowing the rest of the

English to be ransomed."

Fez

"There

it lies, outspread in golden lights, roofs, terraces, and towers sliding over

the plain’s edge in a rush dammed here and there by barriers of cypress and

ilex, but growing more precipitous as the ravine of the Fez narrows downward

with the fall of the river. It is

as though some powerful enchanter, after decreeing that the city should be

hurled into the depths, had been moved by its beauty, and with a wave of his

wand held it suspended above destruction.

At

first the eye takes in only this impression of a great city over a green abyss,

then the complex scene begins to define itself. All around are the outer lines of ramparts, walls beyond

walls, their crenellations climbing the heights, their angle fortresses

dominating the precipices. Almost on a level with us lies the upper city, the

aristocratic Fez Eldjid of painted palaces and gardens, then, as the houses

close in and descend more abruptly, terraces, minarets, domes, and long

red-thatched roofs of the bazaars, all gather around the green-tiled tomb of

Moulay Idriss and the tower of the Almohad mosque of El Kairouiyin, which

adjoin each other in the depths of Fez, and form its central sanctuary."

"One reads of the bazaars of Fez that they have

been for centuries the central market of the country. Here are to be found not only the silks and pottery, the

Jewish goldsmiths’ work, the arms and embroidered saddlery which the city

itself produces, but “morocco” from Marrakech, rugs, tent-hangings and matting

from Rabat and Sale, grain baskets from Moulay Idriss, dagger from the Souss,

and whatever European wares the native market consumes. One looks on the plan of Fez, at the

space covered by the bazaars, one breasts the swarms that pour through them

from dawn to dusk…"

"Step

into Fes’s medina and it’s almost impossible not to be affected by what you

find. Certainly, it may appear to

be disorderly at first, but as your eyes acclimatize, you begin to understand

that there’s very little disorder at all.

The old city moves to an ancient rhythm, a routine that has become

streamlined through time. Like a

shard of once-sharp glass smoothed by decades on the seabed, Fes is sensible,

rounded, complete within itself. "

Shah Tahir, In Arabian

Nights: A Caravan of Moroccan Dreams

"A

walled lane leads down from Bab F-touh to a lower slope, where the Fazi potters

have their baking-kilns. Under a

series of grassy terraces overgrown with olives we saw the archaic ovens and

dripping wheels which produce the earthenware sold in the souks…It is…stacked

on the red earth under the olives, the rows of jars and cups, in their unglazed

and unpainted state…"

Edith

Wharton, In Morocco

"The donkey I couldn’t forget was coming

around a corner in the walled city of Fez, Morocco, with six color televisions

strapped to his back.

The donkey was small…. The televisions,

however, were big—boxy tabletop sets, not portables… The donkey stood squarely

under this staggering load. He walked along steadily, making the turn crisply

and then continuing up the smaller path, which was so steep that it had little

stone stairs every yard or two where the gain was especially abrupt. I caught

only a glimpse of his face as he passed, but it was utterly endearing, all at

once serene and weary and determined.

This encounter was a decade ago, on my

first trip to Fez, and even amid the dazzle of images and sounds you are struck

with in Morocco—the green hills splattered with red poppies, the gorgeous tiled

patterning on every surface, the keening call from the mosques, the swirl of

Arabic lettering everywhere—the donkey was what stayed with me. It was that

stoic expression, of course. But even more, it was seeing, in that moment, the

astonishing commingling of past and present—the timeless little animal, the

medieval city and the pile of electronics—that made me believe that it was

possible for time to simultaneously move forward and stand still. In Fez, at

least, that seems to be true.

I realized I had fallen in love with

donkeys in general, with the plain tenderness of their faces and their attitude

of patient resignation and even their occasionally baffling, intractable moods…

In Morocco, I knew that the look of resignation was often coupled with a

bleaker look of fatigue and sometimes despair, because they are work animals,

worked hard and sometimes thanklessly. But seeing them as something so

purposeful—not a novelty in a tourist setting but an integral part of Moroccan daily

life—made me love them even more, as flea-bitten and saddle-sore and scrawny as

some of them were."

"One reads of the bazaars of Fez that they have

been for centuries the central market of the country. Here are to be found not only the silks and pottery, the

Jewish goldsmiths’ work, the arms and embroidered saddlery which the city

itself produces, but “morocco” from Marrakech, rugs, tent-hangings and matting

from Rabat and Sale, grain baskets from Moulay Idriss, dagger from the Souss,

and whatever European wares the native market consumes. One looks on the plan of Fez, at the

space covered by the bazaars, one breasts the swarms that pour through them

from dawn to dusk…"

Edith

Wharton, In Morocco

"Featureless

walls of…houses close in again at the next turn; but a few steps farther

another archway reveals another secret scene. This time it is a corner of the jealously guarded court of

ablutions as the great mosque El Kairouiyin, with the two green-roofed

pavilions that are so like those of the Alhambra.

Those

who have walked around the outer walls of the mosque of the other Kairouan, and

recall the successive doors opening into the forecourt and in the mosque

itself, will be able to guess at the plan of the church of Fez. The great Almohad sanctuary of Tunisia

is singularly free from parasitic buildings, and may be approached as easily as

that of Cordova, but the approaches of El Kairouiyin are so built up that one

never knows at which turn of the labyrinth one may catch sight of its court of

fountains, or peep down the endless colonnades of which the Arabs say: 'The man

who should try to count the columns of Kairouiyin would go mad.'

Marble

floors, heavy whitewashed piers, prostrate figures in the penumbra, rows of

yellow slippers outside in the sunlight—out of such glimpses one must

reconstruct a vision of the long vistas of arches, the blues and golds of the

mirhab, the luster of bronze chandeliers, and the ivory inlaying of the

twelfth-century minbar of ebony and sandalwood.

No

Christian footstep has yet profaned Kairouiyin…"

Leaving

Fez and travelling south, the road winds upward into the Middle Atlas Mountains

where we see terraced hills and oak forests. There is an alpine feel to the air as one crests the hills

and comes to open pastureland where sheep graze minded by a lone shepherd. Stone walls create a border between

upland meadow and stand of evergreen trees.

Nomadic

people roam higher, rockier landscapes herding their sheep and goats over vast

stretches of land. Temporary tents

attest to small, temporary settlements.

Scattered patches of snow touch the hilltops and shallow rivulets of

waters reflect the blue of the sky.

Midelt,

an outpost of French colonial occupation and established for the mining of

lead, gypsum, minerals, and fossils, lies on a flat, sandy, high plain between

the Middle Atlas and High Atlas snow-covered mountains.

The

road climbs to 6000 feet, then down to 3000 feet. By afternoon we cross sub-Saharan desert, a dry, chalky

landscape that looked like the American southwest. Every once in a while an old abandoned village (Nezala),

built of clay and straw stands next to or across the street from its newer

incarnation. A few Berber women

and children watch us as we pass.

A man walks beside a mule or two on the side of the road.

There

is a haze in the air, which gets more dense at the afternoon goes by. Curvilinear striations along the

mountainsides attest to cataclysmic geological formations. Arriving at the Valley of the Ziz River

we begin to see the river, but the landscape is one of amazingly tall, jagged

mountains whose tall peaks are silhouetted against the setting sun. We go through mountain passes that

follow the curve of the river as it cuts its way through grand canyons.

Toward

evening we stop along the roadside and, looking out over the valley below, we

see an oasis of date palms, olive, and fig trees that stretches all the way to

the Sahara.

Erfoud

is the jumping off point for visiting the sand dunes of Erg Chebbi on the edge of

the Sahara. It’s an oasis town in the desert and while this watercolor suggests

the vegetation provided by the river Ziz, it also hints at the barren, sandy

terrain where fossils abound attesting to the fact that this was once an ocean

floor. The area has been

identified as being very similar to certain areas on the planet Mars.

Stretches

of land are covered with sandy mounds as far as the eye can see. They are an early underground aqueduct system

designed to carry water through this dry land.

"There were essentially two routes or systems of routes crossing

the Sahara by the mid-eighth century. The most important connected the

Maghrib to Ghana, where Muslim merchants sought gold, slaves,

ivory, and ostrich feathers. The westernmost route went directly to

Audaghust, and a more eastern route went to Ghana by way of the salt mines

of Teghaza, halfway across the desert. Both routes converged at Sijilmasa

in the Tafilelt Oasis in southeastern Morocco.

The Moroccan traveler Ibn

Battuta stayed in Sijilmasa on his journey to visit the Mali Empire (Timbuktu)

in 1352-1353. He wrote: “I reached the city of Sijilmasa, a very beautiful

city. It has abundant dates of

good quality. The city of Al-Basra

is like it in the abundance of dates, but those of Sijilmasa are superior. Ibn Battuta also mentions Sijilmasa when

describing the Chinese town of Quanzhou: “In this city, as in all cities in

China, men have orchards and fields and their houses in the middle, as they are

in Sijilmasa in our country. This

is why their towns are so big.

Leo Africanus, who,

travelling to Morocco in the early 16th century, goes to the

Tafilalt oasis and finds Sijilmasa destroyed. He remarks on the “most stately and high walls,” which were

apparently still standing. He

continues to describe the city as “gallantly builte,” writing there were many

stately temples and colleges in the city, and water wheels that drew water out of

the river Ziz. Leo Africanus says that since the city was destroyed, former residents

had moved into outlying villages and castles. He stayed in this area for seven months, saying that it was

temperate and pleasant. According

to Leo Africanus, the city was destroyed when its last prince was assassinated

by the citizens of Sijilmasa, after which the populace spread across the

countryside.

Ibn Khaldoun says in his

Muqaddimah that the city fell due to a lack of resources. Oral tradition preserved by those in

the Tafilalt says that the “Black Sultan,” a malevolent dictator, was

overthrown by the populace."

Sijilmasa, Wikipedia

"Immediately when you arrive in Sahara, for the first or the tenth

time, you notice the stillness. An incredible, absolute silence prevails

outside the towns; and within, even in busy places like the markets, there is a

hushed quality in the air, as if the quiet were a conscious force which,

resenting the intrusion of sound, minimizes and disperses sound straightaway.

Then there is the sky, compared to which all other skies seem fainthearted

efforts. Solid and luminous, it is always the focal point of the landscape. …

Presently, you will either shiver and hurry back inside the walls, or you will

go on standing there and let something very peculiar happen to you, something

that everyone who lives there has undergone and which the French call 'le

bapteme de solitude.' It is a unique sensation, and it has nothing to do with

loneliness, for loneliness presupposes memory. Here in this wholly mineral

landscape lighted by stars like flares, even memory disappears... you have the

choice of fighting against it, and insisting on remaining the person you have

always been, or letting it take its course. For no one who has stayed in the

Sahara for a while is quite the same as when he came."

Paul Bowles, Their Heads are

Green and Their Hands are Blue: Scenes from the Non-Christian World -- A

Collection of Essays, First Published 1957

The

village of Tinehir, also called Tinghir, sits on a rocky outcrop high above a

palm grove that abounds with olive, fig, pomegranate, almond, and fruit trees

as well as a series of riverside terraces green with fields of spring-growing

wheat and alfalfa.

Ancient crumbling walls of

Ksar Tinghir are what remain of the original ancient fortress. They sit next to the Women Street,

which bustles with vendors of rugs, bejeweled kaftans, ornamented belts and

trimmings as well as sporty Adidas clothing. Tucked here and there are shops selling sheets of decorative

patterns to henna hands and feet. Down

the street craftsmen making bellows, sieves, and ironwork products practice

their trades in open-fronted workshops.

At the edge of the market are vendors of hardware and household goods

and beyond them fruit and vegetable vendors line the streets with a colorful

array of lemons, limes, oranges, strawberries, onions, potatoes, greens, and

sacks of beans, lentils, and spices.

On the southern slopes of

the High Atlas Mountains and some miles from Tinghir, the Todra River meanders

through the 1000 foot Todra Gorge.

At times the adobe walls of the tiny village set deep in the gorge glow

with the warmth of the overhead sun while at others the vertical limestone

walls cast deep shadows. Only a

sliver of blue sky is reflected in the slow-running river.

In Unforgettable: The

Bold Flavors of Paula Wolfert’s Renegade Life, Emily Kaiser Thelin writes

about Paula Wolfert, cookbook writer and author of the 1973 landmark Couscous

and Other Good Food from Morocco. She describes a 1959 trip to Marrakech

during which she “marveled at women washing clothing in a river by the road and

at a man in a djellaba, the traditional long, hooded robe worn by men and

women, walking alongside his donkey.”

Today Morocco is still a

land of contrasts, modern and traditional practices side by side.

This wonderful collaged

image of a veiled woman was hanging on the gift shop wall in the Taourirt

Kasbah. I only had time to

photograph it. I wish I knew the

artist’s name and that I had thought to purchase it.

The Taourirt Kasbah, once

home to the mighty Glaoui family, has been restored and captures the intricacy

and beauty of the palace’s architectural and artistic craftsmanship.

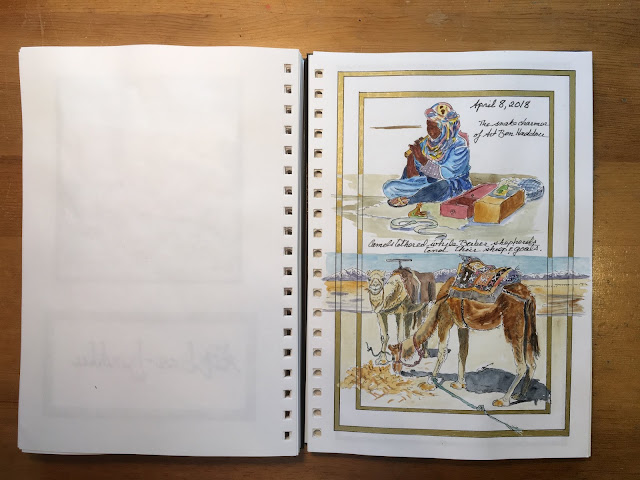

Ait Ben Haddou. A World Heritage site. It has lived in my imagination ever

since I decided to go to Morocco and I was eager to see its deep-red kasbahs

and explore its narrow, now uninhabited streets. There was a distinct possibility that we would not be able

to go into the town because of the fragility of the site, but, nevertheless, I

was disappointed to only catch this glimpse from across the river valley.

"Everyone

said that Marrakech, also known as Al-Hamra, or the Red-Walled City, had

nothing in common with Fez, which was located too near the Christian frontier

and the Mediterranean, and was swept by too many bitter cold winter winds. Marrakech, on the other hand, was

deeply tuned to the African currents, and we heard many wondrous things about

what it was like. Not many in our

courtyard had seen Marrakech, but everyone knew one or two mysterious things

about it.

The

walls were flaming red in Marrakech, and so was the earth you walked on. Marrakech was blazing hot, and yet

there was nearly always snow up above it, shining on the Atlas Mountains. In ancient times, you see, Atlas had

been a Greek god living in the Mediterranean Sea. He was a Titan fighting against other giants, and one day he

lost an important battle. So he

came to hide on the African shores, and when he lay down to sleep, he tucked

his head into Tunisia and stretched his feet as far as Marrakech. The “bed” was so nice that he never

woke up again, and became a mountain.

Snow visited Atlas regularly each year for months, and he seemed to be

enchanted to feel his feet trapped in the desert, and twinkled to passerbys

from his royal captivity.

Marrakech

was the city where black and white legends met, languages melted down, and

religions stumbled, testing their permanence against the undisturbed silence of

the dancing sands."

Fatima

Mernissi, Dreams of Trepass

"My

darling Clemmie,

This

is a wonderful place, and the hotel one of the best I have ever used. I have an

excellent bedroom and bathroom, with a large balcony twelve feet deep, looking

out on a truly remarkable panorama over the tops of orange trees and olives,

and the houses and ramparts of the native Marrakech, and like a great wall to

the westward the snowclad range of the Atlas mountains—some of them are nearly

fourteen thousand feet high. The light at dawn and sunset upon the snows, even

at sixty miles distance, is as good as any snowscape I have ever seen. It is

five hours to the ridge of the Atlas and they say you then look down over an

immense area, first a great tropical valley, then another range of mountains,

and beyond all the Sahara desert.

How

I wish you were here. The air is cool and fresh for we are 1500 feet high, yet

the sun is warm and the light brilliant.

Tender

love my darling one

From

your ever loving husband"

"In Marrakech, night falls in the blink of an eye. I glanced up at the canvas of stars

glinting above, mirroring the butane lamps on the food stands below. Sheep were roasting on a thousand

homemade stalls, oily smoke rising heavenward, conical clay tangines sizzling

like firestorms from Hell.

Jemaa al Fna is the heart of Marrakech. By day’s it’s a turbulent circus of life—teeming with

astrologers, healers, storytellers, and acrobats. And when the curtain of dusk shrouds the city from the

desert all around, the food stalls flare up, creating a banquet for the senses.

With its outlandish customs, Jemaa al Fna is a focal point of

folklore, a borehole than descends down through layers and sub-layers of

Morocco’s underbelly. A lifetime

of study couldn’t teach you all it represents. To understand it, you must try not to think, but to allow

the square’s raw energy to be absorbed directly through your skin."

"The Djema’a el-Fna covers a wide area… They say it has existed as

long as the Koutoubia which looks down on it from the end of a vista—and that

means the twelfth century… They also say that it is never empty… It has a

strange quality and when you look closer you find that the sky seems to sail

above it as if the two were part of the same cosmic plan. It has something of the sea, an inland,

tideless sea, waves of djellaba-hoods,… moving closely together, so close that

identities merge into a general turbulence.

It was simply a fairground again: singers, an ostrich standing

among the bones of its fellows, a woman who drinks boiling waters from a kettle

to the accompaniment of flutes.

Boys—Chleuhs, someone told me…pirouetting and squeaking and clinking

their minute finger-cymbals,… tumblers, the fire-eaters, the

charmeurs-de-serpent…"

Tahir Shah, Marrakesh: Through Writers’ Eyes

"Five days later I found myself standing in Jemaa al Fna, the vast

central square in Marrakech whose name means “Place of Execution.” The medina’s labyrinth of narrow

covered alleys stretched out behind in an endless honeycomb of riches. Every inch of it bustled with brass

lamps, silks, and rugs woven in kaleidoscopic colors, spices and perfumes,

sweetmeats and dried chameleons for use in spells. The shade of the medina was contrasted by the searing light

in the square."

"Now, I wish I could tell you the wonder of the

souks and marketplaces; the brilliant overflowing of spices, olives, fabrics;

the witchcraft stalls; the fishmongers; the piles of mint and thyme scenting

the air . . ."

“’Riad’”

simply means garden, and is used to describe a house with a central courtyard,

typically for four symmetrical flower beds inside. The flower beds signify the world beyond, for Muslims

believe that Paradise is a garden.

Any visitor to the Arabian desert can imagine how the nomadic Bedouin

would have fantasized about such a place, with cool shady trees, birdsong, and

fountains issuing an abundance of fresh water.”

“The

palaces of their overgrown gardens, with pale-green trellises dividing the

rose-beds from the blue-and-white tiled paths, and fountains in fluted basins

of Italian marble, all had the same drowsy charm…

Court within cour, garden beyond garden, reception halls, private apartments, slaves’ quarters, sunny prophets’ chambers on the roofs and baths of vaulted crypts, the labyrinth of passages and rooms stretches away over sever acres of ground. A long court enclosed in pale-green trellis-work, where pigeons plume themselves about a great tank and the dripping tiles glitter with refracted sunlight, leads to the fresh gloom of a cypress garden, or under jasmine tunnels bordered with running water; and these again open on arcaded apartments faced with tiles and stucco-work, where, in a languid twilight, the hours drift by to the ceaseless music of the fountains.

On each side of the atrium are long inner rooms closed by vermilion doors

painted with gold arabesques and vases of spring flowers…”

“A visit to Marrakech was a

great shock to me. This city

taught me colour…”

Yves St. Laurent

“We quickly became very

familiar with this garden, and went there every day. It was open to the public

yet almost empty. We were seduced by this oasis where colours used by Matisse

were mixed with those of nature. » … « And when we heard that the garden was to

be sold and replaced by a hotel, we did everything we could to stop that

project from happening. This is how we eventually became owners of the garden

and of the villa. And we have brought life back to the garden through the years.”

Pierre Bergé, Yves Saint Laurent, “Une passion marocaine”

Éditions de

la Martinière, 2010

Casablanca. “Play it again, Sam.” Visions of Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid

Bergman, a nightclub—Rick’s Café Americain, piano music at the bar, love,

sacrifice, and escape. These are

what come to mind when thinking of Casablanca.

It is, however, the

vision of a churning, rolling, wave-breaking Atlantic shore line with the

weather changing moment to moment from misty and moisture-laden to clear, streaming

sunlight that will forever remain a memory of Casablanca for me.

Far down the shore, built

over water and land, rises the 60 storey high minaret of the Hassan II Mosque,

which can hold up to 25,000 people in its vast, marbled prayer hall where the

roof can open to the sky above.

Mosque and minaret were built in honor of the king's father to “reflect the

fervor and veneration with which this illustrious man was regarded.”

To make clear his vision,

he said:

“I wish Casablanca to be

endowed with a large, fine building of which it can be proud until the end of

time… I want to build this mosque on the water, because God’s throne is on the

water. Therefore, the faithful who

go there to pray, to praise the creator on firm soil, can contemplate God’s sky

and ocean.”

Six thousand traditional

Moroccan artisans worked for five years to create the mosque building with its

marble, mosaics, plaster moldings, carved and painted ceilings.

A modern sensibility is

brought to the traditional tile work, called zellige, much of it “sea-foam green

and God’s blue.”

In preparation for my trip

to Morocco, I became interested in Persian illumination. This was my attempt at reproducing a

page from the Walters Art Museum’s manuscript W.559 made in the year 1323 AD by

Mubarakshah ibn Qutb known as “The Golden Pen.”

A selfie of myself

wrapped in my Moroccan shesh (Tuareg turban) taken just before driving into the

desert to the place where I would ride my camel up the top of the dunes to see

the sun set over the Sahara. April

6, 2018